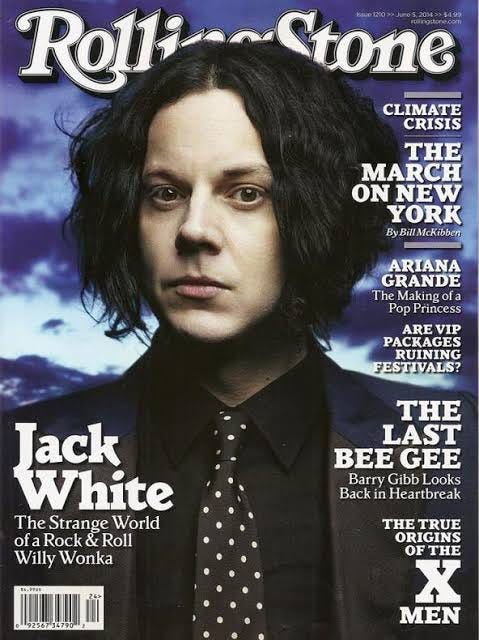

Growing up I was an avid reader of Rolling Stone. Multi-page interviews with idols such as Jack White, Harry Styles and Lana Del Rey were treasured insights into the minds and lives of my icons. I would study every piece of writing in the magazine, even the reviews of albums I would probably never listen to. I took every new edition as a chance to learn.

Maybe I’ve changed, or maybe the world around me has, but music media is not what it once was.

The most excited I get to read a review is when I hear of anything under than 5/10 on Pitchfork. Admittedly, there is some twisted part of me that likes to read well written, sarcastic remarks.

I might click on a Needle Drop video when it appears in my feed, but only to jump to the description. I only really care about the album’s rating and Fantano’s list of fave and least fave tracks.

Ok… maybe I’ve changed. Maybe I’m part of the problem.

Our fascination with the individual has shaped contemporary music criticism, which now focusses more on the artist than the music. Especially when discussing the output of female artists.

In a quick survey of Pitchfork reviews, I’ve found two through lines

Music by women is generally assessed based on its lyrical content rather than its musical or production elements

Female artists face more character questioning (with her aggrievances considered annoying or tired) than their male counterparts.

For most women in music, this is not breaking news. Shock horror: the industry is against you!

Post brat summer (pre Australian brat remix summer), and with the meteoric rise of Sabrina & Chappell, this reality has been somewhat clouded.

“Pop is back! Music is for the girls!”

Well, sort of.

Generally, the industry, the internet, and The People (whoever They are) handpick a few women who are in favour. The ones allowed to succeed in that moment. The handful who are ‘doing it right’ while the rest are embarrassing themselves.

Women who’s careers have lasted long enough - Taylor, Lana - spent years out of favour until it was unfashionable to hate on them. (And now somehow even the most sloppy song is lauded).

-As an aside, I do want to point out that all these artists work almost exclusively with male producers. But that is beside my central point today-

The regeneration of my rage at music criticism was sparked by Halsey. An artist who I have never found particularly interesting and regularly forget about, despite being one of the biggest in the world, statistically. (I’ve never met a Halsey fan IRL but they clearly do exist… somewhere).

Halsey’s recent album, The Great Impersonator, suffered a 4.8/10 from Pitchfork via Shaad D’Souza and a horrific 1/10 from The Needle Drop (aka Anthony Fantano).

I don’t think a concept can save an album from mediocre writing and uninspired production, but is important context when reviewing a body of work. At a time where feminism is trendy, you’d think Shaad and Fantano may have done a little more work into understanding medical misogyny before composing entire reviews on an album unpacking just that.

In the last few years, Halsey has been diagnosed with a string of health conditions, namely Lupus. Lupus is an autoimmune disease that can cause body aches, tiredness, hair loss, fever, the list goes on.

Autoimmune diseases disproportionately affect women, and on average take 4-7 years to diagnose. That is 4-7 years of going to appointments, explaining your symptoms, being told there is nothing wrong with you, all while suffering extreme physical pain and having to continue life as if nothing were wrong.

This is the backdrop for Halsey’s The Great Impersonator, a lyrical and musical concept toying with lupus’ title as the great imitator (like many autoimmune diseases, it’s symptoms replicate those of several other health issues).

Halsey took the title and ran with it. Each song is supposed to be written in the style (and perspective?) of a different musical icon. We’ve got Bowie to Björk, Britney to Dolly. You get the picture.

It’s an ambitious concept, I’ll give them that. Musically and lyrically, I’m not sure I could identify these inspirations without being told. But it would almost be stranger for the tracks to sound like perfect replicas.

Shaad and Fantano seem so hung up on Halsey’s failure to imitate her references that they willingly ignore her real life context. Moreover, they struggle to read into the notion of imitation and perhaps the intentionality of her failure at it. (Halsey has spoken of feeling like a professional imitator, trying to be someone she is not while being betrayed by her body and thinking she was going to die).

Maybe, like the medical professionals, Shaad and Fantano just don’t believe Halsey’s health concerns are that serious.

Quite frankly, both reviews read as lazy journalism.

In what can only be described as extremely poor taste, Fantano accuses Halsey of having “the worst case of main character syndrome”.

Shaad seems to think Halsey is too swept up in her own victimhood, and that their “indulgently sad veneer hides a convenient rejection of its author’s own agency”.

Is a woman writing about suffering an autoimmune disease too whiny for these guys?

I genuinely cannot imagine any male artist receiving this response while writing from such a vulnerable state. (I also can’t think of any records by a male artist detailing him not being believed by medical professionals… coincidence?).

Both reviews are so insistent on accusing Halsey of ‘complaining’ that they forget to offer any interesting critique of the music itself. They don’t even touch on any vocal or songwriting analysis, with Shaad quoting the lyrics twice and Fantano once.

Both reviewers seem to take excessive issue with Halsey writing about her life and her fear of losing it.

They also both manage to neglect any acknowledgment of her musings on motherhood, the love for her son, and her fear of him growing up without a mother.

Instead, Pitchfork and The Needle Drop seem to revel in the opportunity to assassinate the character of a woman lamenting her health.

Music criticism has sadly become a place for media outlets and reviewers to celebrate the artists in vogue at any given time. Less interested in the music and more interested in being favoured by the masses, music writers rarely seem to say much about the music itself.